The House of Representatives on Wednesday unanimously passed a bill that threatens to delist Chinese companies such as Alibaba Group Holding and JD.com from U.S. exchanges unless U.S. regulators are able to inspect their financial audits within three years.

Of the China-related measures introduced in recent months, the bill could have the broadest impact on investors’ portfolios—though the logistics to implement the measures likely means the fallout won’t be sudden or as drastic as it may sound.

With the House vote, the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act bill goes to President Donald Trump, who is expected to sign the measure.

The Senate already passed the bill over the summer. The Securities and Exchange Commission has also been working on a related proposal that The Wall Street Journal reported would put the responsibility on exchanges to require audit inspection compliance.

Shares of KraneShares CSI China Internet ETF (ticker: KWEB), which has several U.S.-listed Chinese stocks among its top holdings, fell 0.51% after hours to $73.80. Shares of JD.com (JD), which closed down 1% at $84.38, and Alibaba (BABA), which closed down 1% at $261.32, slipped further in after-hours trading.

The delisting push comes amid a spate of measures aimed at China as the relationship between the two countries undergoes a reset. But this bill addresses longstanding issues around disclosures, transparency and accountability, including limitations on foreign oversight of its companies.

Investors are grappling with the increased regulatory and geopolitical risks at the same time strategists are recommending they allocate more to China as its economy is further along its recovery from the pandemic.

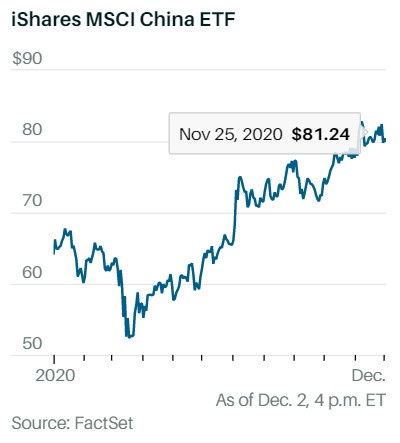

The iShares MSCI China exchange-traded fund (MCHI) is up almost double the S&P 500 index year-to-date, and 36 Chinese companies have gone public this year in the U.S., according to Renaissance Capital, up from 25 a year earlier. Taking a selective approach and factoring in risks may increasingly be the answer rather than dumping all things China.

China’s Recovery

The bill won’t come as a surprise to investors. Emerging markets fund managers have been swapping U.S. listings of widely held stocks like Alibaba Group Holding (BABA), JD.com (JD), NetEase (NTES) for their secondary listings in Hong Kong listings for months, in anticipation of the measure. And some of the highest-valued Chinese companies have sought secondary listings, with 30 of the roughly 190 U.S. listed Chinese companies having that as a safety net.

Retail investors can also access those listings. For example, Interactive Brokers offers access to 135 markets, including Hong Kong, and allows trade in 23 currencies; Fidelity offers its investors direct access to 25 foreign markets, including Hong Kong, with settlement in 16 currencies. Schwab clients that want to trade on local markets like Hong Kong in the local currency directly can do so through a global account.

But more than 100 companies still don’t have another listing yet, including popular electric vehicle stocks like Tesla rival Nio (NIO), and Xpeng (XPEV). Here, one framework may be to think about Brexit. “If you convinced yourself Brexit was happening tomorrow and you better act, you would have been premature by two to three years,” says Patrick Chovanec, economic advisor at Silvercrest Asset Management. “I’ve always argued that a lot of these companies don’t belong on U.S. exchanges but that doesn’t mean you pull the rug out. The three-year time horizon creates a framework for the U.S. and China to negotiate. They will have three years to develop an off-ramp for companies that can’t meet compliance.”

Another reason few expect immediate selling: Investors are likely to monitor whether the new administration has better luck at seeking a compromise with China over auditing—though most analysts assign a low probability to such a truce.

An Alibaba spokesperson referred Barron’s to comments from Alibaba Chief Financial Officer Maggie Wu after the Senate bill passed unanimously this summer. At the time, Wu indicated the company would try to comply with any legislation and reiterated that Alibaba’s financial statements have been prepared in accordance with U.S. accounting standards and audited by PwC Hong Kong since 1999. She also noted that the Big Four accounting firms were in discussions with Chinese and U.S. regulators, including the U.S. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, on the types of information that could be exchanged while staying in compliance with Chinese laws.

TS Lombard economist Rory Green expects most U.S.-listed Chinese companies to comply and avoid delisting.

But if that’s not the case, Chinese companies looking to list closer to home would have to meet listing requirements, which range from criteria regarding revenue, market cap, float and management continuity. They may, however, find a more hospitable backdrop. The Hong Kong stock exchange has already amended rules to make more companies eligible to list there and mainland Chinese exchanges, including the Nasdaq-like STAR board in Shanghai, are also making to changes to make the domestic market more attractive to Chinese tech companies, says Wechang Ma, portfolio manager at global investment manager NinetyOne, which oversees more than $140 billion in assets, via email.

If companies that currently have secondary listings in Hong Kong leave the U.S., and the Hong Kong listing turns into a primary listing, these companies could become eligible for the southbound Stock Connect program that gives mainland investors access to stocks listed in Hong Kong.

That could be beneficial longer-term for some of these companies, with domestic investors showing a willingness to pay higher valuations at times for Chinese technology companies listed in Hong Kong than international investors pay for peers listed in the U.S., Ma says.

Ultimately, the delisting push could create a two-tier version of Chinese stocks—those with secondary listings or that can secure a listing in Hong Kong or mainland China and are big enough household names to draw investor interest and plenty of liquidity and possibly a smaller batch of companies that don’t meet listing restrictions or find little liquidity. Some of those companies could go private, possibly at lower valuations.

More worrying for investors though could be measures that ratchet tensions higher between the two countries. Among clients, especially hedge funds, Henrietta Treyz, director of economic policy research at Veda Partners, says the most interest is in measures that could provoke a retaliatory response, like pushing China to populate its own blacklist with U.S. companies. The delisting bill doesn’t fall into that category.

Analysts expect Beijing to take a wait-and-see approach in coming months as they try to assess the Biden administration’s approach. While stimulus and the pandemic are likely to be the initial focus of the administration, Treyz notes that China is one of the few areas of bipartisan support—opening the door longer-term to a more expansive China-related bill that tackles issues on multiple fronts, across agencies, including human rights, climate change digital taxes and opening access to certain markets—areas where the progressive part of the Democratic Party and the more hawkish Republicans could possibly find common ground.

That means assessing China-related risk will be a skill investors want to hone for 2021—and beyond.

www.marketwatch.com, 2 Dec 2020