The selling of stocks accelerated this month, leaving Americans with less wealth to scramble for cash

Published: March 26, 2020 at 5:35 a.m. ET, By Beth Kindig

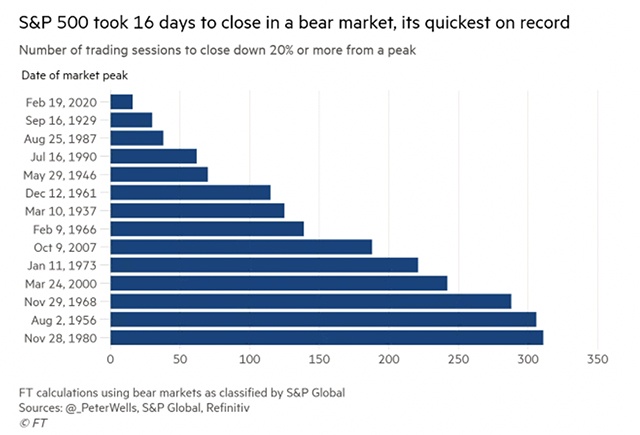

The U.S. stock market’s plunge this year has been faster than at any other time in history.

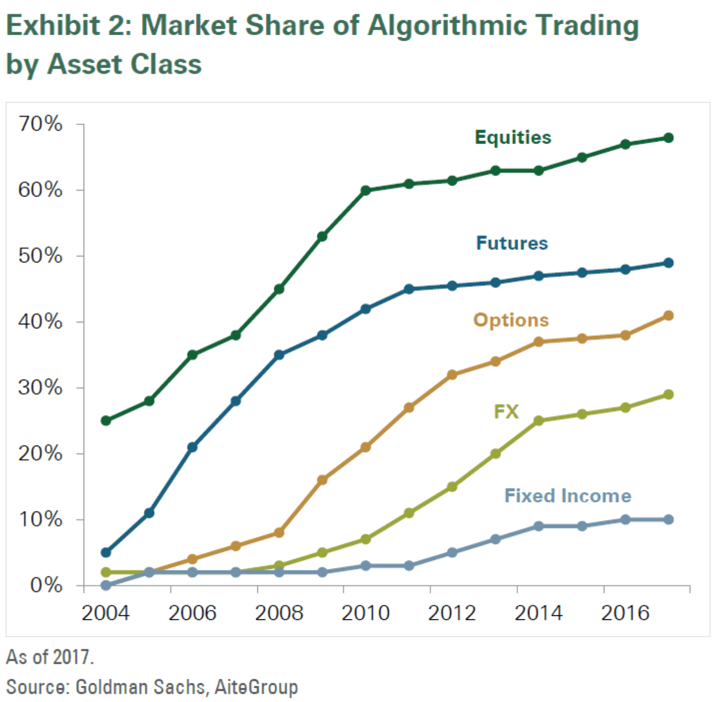

What’s driving the speed and severity of the bear market is the escalation of algorithmic trading, which is more prevalent than it was during the Great Recession in 2008. Sadly, wealth preservation is at stake as funds in retirement accounts compete, and are defeated, by programmed machines.

Going downhill fast

March 2020 holds the record for how quickly stock prices dropped into a bear market — only 16 days after the S&P 500 Index SPX hit its last closing high Feb. 19. The second-fastest bear market was the notorious 1929 crash that set off the Great Depression, followed by the elevator drop of 1987’s Black Monday. A bear market is usually defined as a 20% decrease in prices.

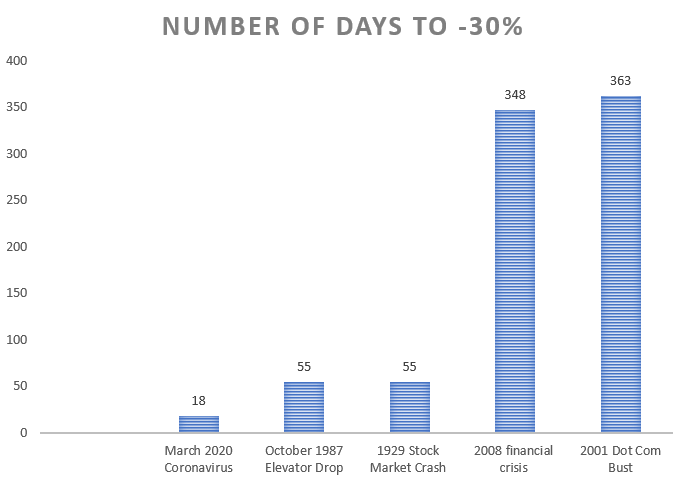

How long did it take for stocks to plummet 30%? Nineteen days this year, and a tie for second place between the crashes of 1929 and 1987 — 55 days. During the dot-com bust in 2000 and the 2008 meltdown, it took almost a full year for stocks to retreat 30% from their highs.

Americans invested in stocks through 401(k)s and other retirement accounts may be unaware that they are part of a small minority of investors who are in it for the long run. Guy De Blonay, a fund manager at Jupiter Asset Management, said 80% of the stock market was controlled by machines during the selloff in 2018’s fourth quarter. In 2017, analysts at J.P. Morgan said “fundamental discretionary traders” accounted for only 10% of stock trading volume.

Despite evidence of negative consequences, rampant algorithmic trading has become accepted as the new norm. However, this is the first time algorithmic trading may compound an economic recession, as Americans pull money from retirement accounts to access cash.

In fact, the government is helping Americans get easier access to cash: The coronavirus-relief bill would waive the 10% early-withdrawal penalty for distributions up to $100,000 from qualified retirement accounts.

On March 19, President Trump warned that the country could face 20% unemployment, which would it put it on par with the Great Depression, at 24.9% joblessness. As we saw in 2008, massive unemployment forces the middle class to withdraw from their retirement accounts to pay bills. This time, the middle class will have less money to pull. The Federal Reserve is a player here, as the central bank pushed fund managers deep into equity markets to keep up with inflation.

Last week, Reuters reported that more retirees in Florida are worried about the stock market collapse than they are about the coronavirus. This is despite the virus being especially deadly to the elderly.

Pros can’t compete

Some of the best financial minds also are losing to machines. Philippe Jabre, one of Europe’s best-known hedge fund managers for generating outsized returns, returned client capital in three hedge funds in December 2018.

In a letter to shareholders, Jabre wrote: “Financial markets have significantly evolved over the last decade, driven by new technologies, and the market itself is becoming more difficult to anticipate as traditional participants are imperceptibly replaced by computerized models.”

Other money managers who thrived in previous decades have recently closed their hedge funds, including Louis Bacon of Remington Funds; Jeffrey Vinik, previously the manager at Fidelity’s Magellan fund; and Leon Cooperman of Omega Advisors.

According to Wells Fargo, robots will replace 200,000 banking jobs over the next 10 years. Citigroup C has formed a lab to cross-train traders and developers for machine learning and artificial intelligence. The programming language Python is especially in high demand at leading banks, such as J.P. Morgan Chase JPM and Goldman Sachs GS.

Therefore, the largest financial institutions are positioned to fare well in a market where algorithmic trading dominates. That leaves the average American with even fewer advantages.

More evidence of algo damage

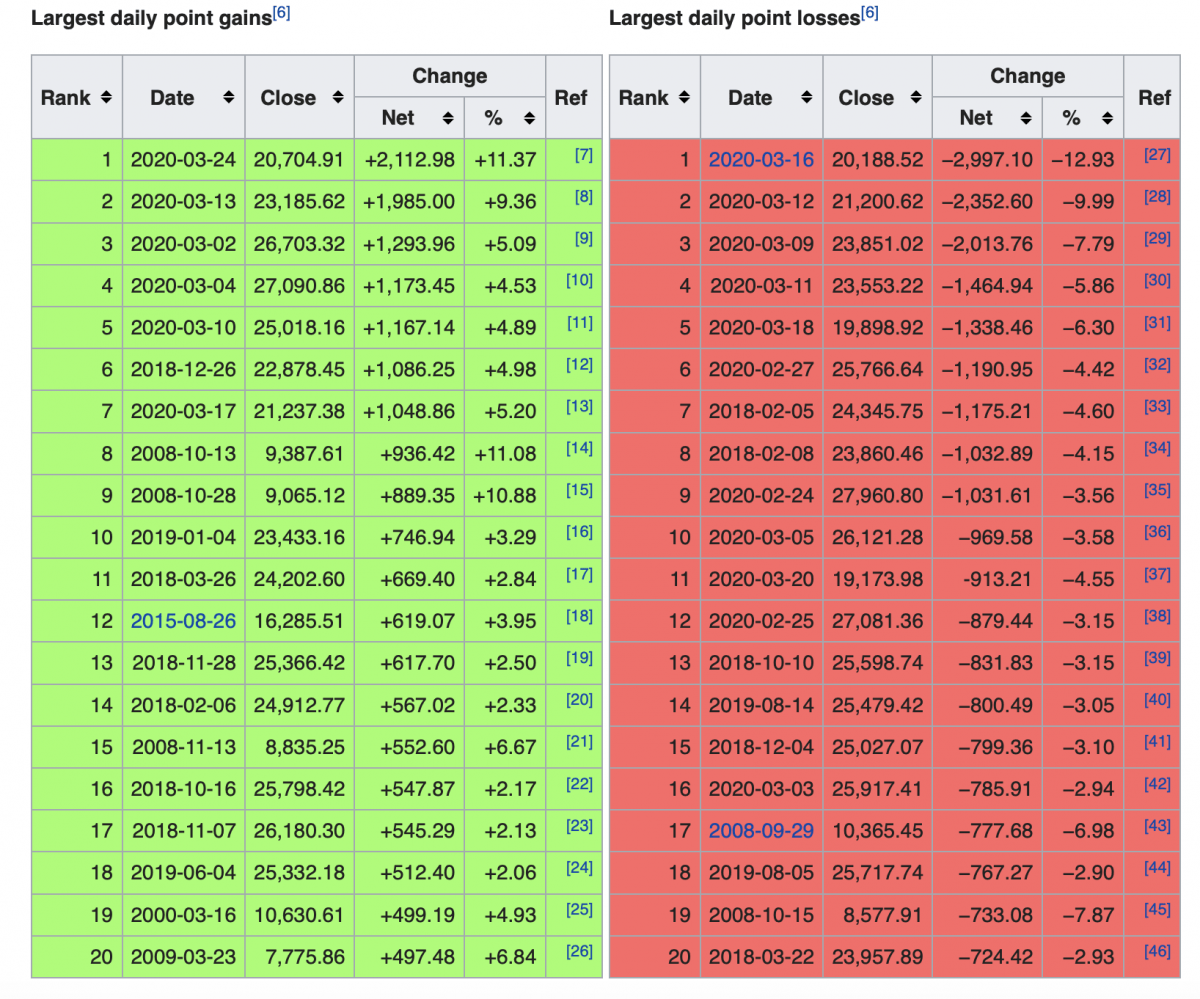

When a large institution buys or sells a large position, computer algorithms find price anomalies and trade on the other side of it. This is one reason a large majority of intraday records were broken this month.

The market may be down 30%-plus, but machines are feasting on the intraday moves as they “buy the dip” and quickly sell (or buy) in the final hours. These big swings are worth millions of dollars when a machine is timing the intraday entries and exits.

The “flash crash” on May 6, 2010, caused the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA to drop 998.5 points (about 9%) within minutes, only to recover a large part of the decline later in the day.

According to the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), high-frequency trading “did not cause the Flash Crash, but contributed to it by demanding immediacy ahead of other market participants.”

Flash moves of nearly 1,000 points in either direction are now the new normal, with 14 occurring in the past 30 days. Four of those intraday moves were more than 9%. Trading curbs, known as circuit breakers, were hit four times this month.

Not a level playing field

Black swans are defined as unpredictable events that are beyond what is normally expected. However, the severe impact of this market selloff extends past that definition. There has essentially been no time for the average investor to adjust.

Perhaps we will get a coronavirus vaccine or antiviral tomorrow, and business will go on as usual. Or, the opposite could happen, and things will get worse. One thing is certain: Until there is regulation, the machines will profit either way.

Beth Kindig is a San Francisco-based technology analyst with more than a decade of experience in analyzing private and public technology companies. Kindig publishes a free newsletter on tech stocks at Beth.Technology and runs a premium research service.

Source: www.marketwatch.com